|

KBC Home

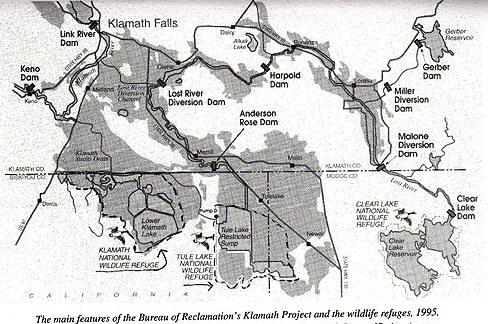

That was assisted by the introduction of the railroad, which built the rail line across the connection between Lower Klamath Lake and Klamath River. In the Klamath Straits was the body of water that carried floodwater into the Lower Klamath Lake and in extremely high water years allowed some water to drain back into the system (not in most years). This area through evapo-transpiration used between 3 and 4 acre feet per acre per year. In addition, you can see that Tule Lake at this time was a large body of water, a large body of open water, and the water that came into Tule Lake came mostly through the Lost River system, all the way around and then coming back into Tulelake.

Building the Project,

rerouting and storing the water for irrigation It also came from the Miller Creek area and to help with the draining in that area the Bureau of Reclamation built dams at what was then called the Horse Fly Reservoir site, which is now Gerber Reservoir and Clear Lake, and basically they built those dams to help evaporate water off so that it wouldnít make it to Tule Lake. So the Bureau of Reclamation came in, took over some existing canal companies, and developed what we have over here. The A Canal was one of our first facilities. We rebuilt the head works and did some work on the canal to help develop that. A Canal delivers water as far east as Harpold Dam, and it also delivers water down into the main heart of the irrigation area which was some of this land that was earlier developed. After we have developed the canal and it was in service for a number of years, we decided that we needed a little bit more storage to be used to make things work, and Link River Dam was built under contract with what was then CopCo, what is now PaciCorp. And they built Link River Dam starting in 1917 and it was completed in 1921. We developed the Reservoirs at Gerber and Clear Lake to stop the water from making it into Tule Lake through the Lost River system. We also deliver water from those facilities now for irrigation purposes through Langell Valley and the Horsefly Irrigation District, down to about this area. Not a lot of water escapes that system during the irrigation year. Harpold Dam is not releasing any water right now, they had a little bit that was coming over after the rain storm that we got, but in most cases Harpold stops Lost River during the irrigation seasons. So, these areas in here, if we want to irrigate them, we have to bring water over from the Klamath River and the Poe Valley and this area is irrigated with water thatís released into A Canal and brought over through the E and the F Canals. The area around Tule Lake was settled by veterans of WWII, it was opened to homesteading at that time. We had had pretty good success in draining the lake and providing the area for entry. The water that would have gone there from the Lost River system had been essentially cut-off by the uses of Langell Valley and Horsefly. So, some water is collected back in drains, and delivered back into the Lost River, and we also have the ability to bring water to the Lost River from the Klamath thru the Lost River diversion channel. The Lost River diversion channel initially was used to take floodwaters to the Klamath River so that they wouldnít make it to Tule Lake during the irrigation season. We can turn it around, itís so flat that it runs both directions, and we deliver water back into the Lost River system down to Tule Lake from that area. In the Lower Klamath Lake area we have a couple of canals that deliver water into that area. We have the AD Canal and the North Canal and those deliver water into areas that for the most part water-up during the wintertime, and they have saturated ground when the growing season starts and they grow grass and they grow grain crops out there with the water that is in the soil profile by and large. There is some water that is delivered during the growing season, mostly for the hay crops that they have out there. And that also delivers water to our lease lands that we manage down here, and we also have lands that are managed under lease in the Tule Lake area. I think that is kind of the gist of the overview. Are there any questions? Refuges, Project efficiency, water use, evaporation and storage

Lesley: We have two refuges that get water from the Bureau of Reclamation; they are where the lakes used to be. We have Tulelake National Wildlife Refuge over here with some of the remaining water from the old Tule Lake, and we have Lower Klamath Lake National Wildlife Refuge over here, which is the remainder of what was generally the open water area of Lower Klamath Lake, below the state line. There is also another wildlife refuge on the other side of Link River that as you were driving up you drove past.

Lesley: Well the entire basin is a surface ground water reservoir, and that is one of the intricacies of the way that we operate the system. If the soil profile isnít full, we donít get the return flows to the drains that we use to be able to re-circulate the water. We use the water that enters the system between 4 and 6 times, before it either ends up in the sumps in the wildlife refuges, or is pumped back out through the Straits Drain back into the Klamath River. The basin has an underlying ground water reservoir that is in pretty good shape right now. We had significant pumping this year and we only heard of a couple of fairly shallow wells that went out of service, due to the pumping that was going on this year. QUESTION: Over what time period were all these sumps built? Lesley: This is one of the earliest projects that the Bureau of Reclamation initiated and construction started in about 1903, and we built most of the facilities by the late twenties. QUESTION: If you had to do it all over again, knowing what you know now, what would you do? Lesley: Iíd do exactly the same thing. I used to argue with John Harper about this when I was there, so itís the way that I feel about it. I think that we have done a good job in this basin. Agriculture uses less water then the basin used before. The water thatís being delivered down stream is more then was in the downstream system previous to the Project. QUESTION: And how do you know that? Lesley: We have records. QUESTION: So prior to 1900s there are records of water flow down the Klamath. Lesley: Yes. And the records that we have show that the water that made it past the Keno reef was almost non-existent in a lot of years during what we call our growing season. We deliver a significant quantity of water pass Keno now, and on down stream into the Klamath River. This tule marsh here was a huge detent; it would just soak up all the water after the flushing flows of the spring and it would hold it, and almost none of it returned. It would stay out here and evaporate off, and there was very little water that would make it past Keno reef during that period.

The Project as a whole is probably in the 90% range of being efficient. So thereís excellent records of how much water comes in, how much is used, and how much goes back out, because of the Bureau Project we have all that data. So there is a lot of supporting evidence that suggest that water going down stream now is probably greater then it was prior to any of these alterations. QUESTION: Cecil, can you talk just a minute what you said about the Bureau deciding they need more storage. Can you talk a little bit about the relationship of the lake to the Link River Dam and how you gain storage there? Lesley: Before we had Link River Dam built, there is a natural reef in the lake that held water up there and that's what caused Upper Klamath Lake to be Upper Klamath Lake. We decided that to make the Project deliver water more frequently during the irrigation seasons, we needed the storage to be able to make that happen. So we put in Link River Dam, which has a head of 12 feet, about 12 feet, and we also had CopCo take a notch out of the reef so that we could access lower into the lake. That has not happened very often, and it hasnít happened recently at all. But we did gain a few feet over the top of what we had before to be able to deliver into the system.

QUESTION: Iíve never quite understood the outflow of this Project. What is it that gets pumped from Klamath Lake to Tule Lake, and what are the relative volumes of that? Lesley: I have those charts over there, mostly to the canals above Anderson Rose and it does deliver into D, which does connect back into J Canal, which delivers into the Tulelake area. But, I canít remember those numbers off hand, but Iíll get them for you.

Lesley: Right, we have a pumping plant called D Plant down here, and when the sumps in Tulelake National Wildlife Refuge get up to a certain level it can threaten the dikes that they have down there, so what we do is that we pump that water over into Lower Klamath Lake through D-Plant, thereís a tunnel through the ridge here and that water can be delivered into the Lower Klamath Lake National Wildlife Refuge, and if thatís full and you need to relieve that of water we have the Klamath Straits Drain, which brings the water all the way back over to the Klamath River. So, we can put water into A Canal, take it all around the system into the sumps through D Plant over into the Lower Klamath Refuge, collect it at the Straits Drain and deliver it back into the Klamath River. Nelson: And you do that? Is that the routine? Is that the way it works? Lesley: Thatís how the system cycles, yes. There is water being pumped out of Straits Drain as we speak, returning to the Klamath River. Water Quality then and now QUESTION: What about the quality issues, with the reuse as it goes through the system, do you track that? Whatís happening to the quality of the water as it goes through the system, after itís been used 4 or 6 times, or whatever? Dr. Ken Rykbost, Superintendent, Klamath Experiment Station, Oregon State University: The Project is a net sink for phosphorus and nitrogen. QUESTION: Well, there are other things besides that, that Iím just curious about? I mean about the salinity. Carlson: There is degradation of water quality typical of any downstream. QUESTION: Those are monitored though?

Carlson: One of the interesting things is, with the drainage and the transport of water to Lower Klamath, the water quality of the water in Tule Lake has actually improved over the length of the Project in terms of salt content. ___________________________________________________

#2 o Conservation

Implementation Program, CIP |